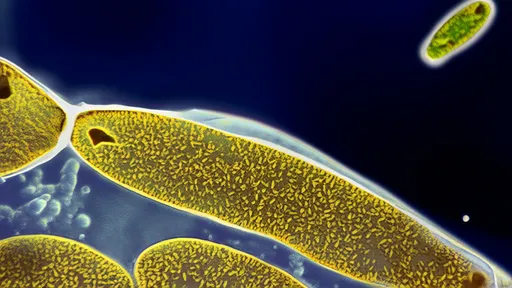

In the evolving landscape of sustainable construction, a microscopic ally is making a monumental impact. Researchers and engineers are turning to nature’s own toolkit, exploring the potential of microorganisms to revolutionize how we build. Among these biological pioneers, Bacillus pasteurii, a common soil bacterium, has emerged as a key player. This bacterium’s unique ability to produce the enzyme urease is being harnessed to develop a novel biological cement, offering an eco-friendly alternative to traditional chemical binders for soil stabilization.

The science behind this innovation is both elegant and efficient. When introduced to a mixture of sand and a solution containing urea and calcium chloride, Bacillus pasteurii gets to work. The urease enzyme it secretes catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea, producing ammonium and carbonate ions. These carbonate ions then react with the freely available calcium ions, precipitating out of the solution as calcium carbonate crystals. It is this very precipitate—the same compound found in limestone, chalk, and seashells—that acts as a natural glue, binding loose sand particles together into a solid, stone-like material.

This process, known as microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP), is more than just a laboratory curiosity. Its applications are vast and particularly promising in the field of geotechnical engineering. Loose, sandy soils are notoriously difficult to build on. They lack cohesion, are prone to erosion from wind and water, and can liquefy during seismic events. Conventional methods to stabilize such ground often involve injecting synthetic chemical grouts or using mechanical compaction, processes that can be energy-intensive, costly, and sometimes harmful to the surrounding environment.

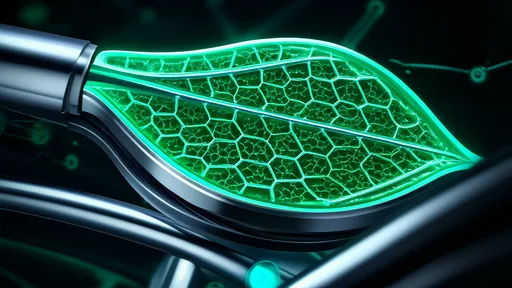

In contrast, the bacterial approach offers a paradigm shift towards green construction. The raw materials—bacteria, urea, and calcium—are naturally abundant and non-toxic. The reaction occurs under ambient temperatures, significantly reducing the energy footprint compared to the production of Portland cement, a major source of global CO2 emissions. Furthermore, the resulting bio-cement is remarkably compatible with its environment, seamlessly integrating with the natural soil matrix without introducing foreign pollutants.

The practical benefits of this microbial glue are already being demonstrated in pilot projects and research studies around the world. One of its most immediate applications is in the reinforcement of foundation soils. By injecting the bacterial solution into the ground beneath existing structures or future building sites, engineers can effectively increase the soil's bearing capacity and shear strength, preventing settlement and subsidence. This is especially valuable in earthquake-prone areas, where stabilizing loose sand can mitigate the risk of liquefaction, a phenomenon where solid ground temporarily behaves like a liquid, with devastating consequences for buildings and infrastructure.

Beyond foundational work, this technology is proving invaluable in the fight against erosion. Coastal areas and riverbanks, constantly battered by waves and currents, are experiencing accelerated erosion due to rising sea levels and increased storm intensity. Applying a layer of bio-cement to these vulnerable slopes can armor them against the elements. The precipitated calcite forms a robust, yet permeable, crust that protects the underlying soil from being washed away while still allowing for natural water drainage and gas exchange, preserving the local ecosystem's health.

The restoration of historical monuments presents another fascinating use case. Many ancient structures, from temples to cathedrals, are built from sandstone or limestone, materials that slowly crumble and crack over centuries of exposure. Conservators face the delicate challenge of repairing this damage without altering the chemical composition or appearance of the original stone. Here, Bacillus pasteurii offers a subtle and sympathetic solution. The bacteria can be applied to damaged areas, where they will catalyze the formation of new calcite that is chemically identical to the original building material. This bio-cement fills cracks and pores, consolidating the structure from within and extending its life for future generations, all while being virtually invisible.

Despite its immense promise, the widespread adoption of this biotechnology is not without its challenges. Scaling up from controlled laboratory experiments to large-scale field applications requires meticulous optimization. Factors such as the uniform distribution of bacteria and reagents throughout the soil mass, the control of reaction rates to ensure even strengthening, and the long-term durability of the bio-cement under various environmental conditions are active areas of research. Scientists are experimenting with different delivery methods, nutrient sources, and even genetically modified strains of bacteria to enhance the efficiency and reliability of the process.

Looking ahead, the potential of microbial construction glue extends far beyond merely binding sand. Researchers are envisioning a future where bacteria are used to create self-healing concrete. Imagine a concrete that can automatically seal its own micro-cracks as they form, drastically prolonging the lifespan of bridges, roads, and buildings while reducing maintenance costs. Other explorations include using different microbes to precipitate minerals that can sequester toxic heavy metals, effectively decontaminating polluted soils—a process known as bioremediation.

The exploration of Bacillus pasteurii and its remarkable enzyme is a powerful testament to the potential of biomimicry. By learning from and collaborating with nature, we are developing solutions that are not only effective but also sustainable and harmonious with our planet. This tiny bacterium is helping to lay the foundation, quite literally, for a new era of construction—one that is smarter, greener, and more resilient. It serves as a compelling reminder that some of the most powerful tools for building our future have been beneath our feet all along.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025