In an era where counterfeit goods cost the global economy over half a trillion dollars annually, the race to develop unbreakable anti-counterfeiting technologies has intensified. While holograms, QR codes, and RFID tags have served as frontline defenses, their vulnerability to replication has spurred innovation in an unexpected direction: biology. The emerging field of biological cryptography now proposes using microbial gene sequences as living, self-replicating security tags—a concept that merges cutting-edge genomics with industrial authentication.

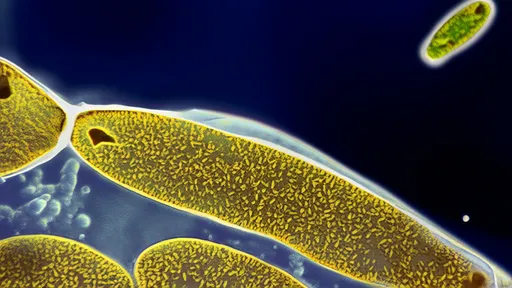

The foundational idea is as elegant as it is complex. Each product or batch is assigned a unique identifier not stored in a database or printed on a label, but encoded into the DNA of a harmless, non-pathogenic microbe. This microbial tag, often a custom-engineered plasmid or a specific genetic signature in a bacterial strain like Bacillus subtilis, is applied to the product or its packaging. The sequence itself acts as a cryptographic key, a biological barcode invisible to the naked eye and incredibly difficult to reverse-engineer or copy without access to the original biological material.

What sets this system apart is its dynamic nature. Unlike static codes or holograms, these microbial tags are alive. They can be designed to respond to environmental triggers. For instance, a tag might express a fluorescent protein only when exposed to a specific chemical developer used by authenticators, providing a visual confirmation of authenticity. Others could be programmed to degrade after a set period, making them perfect for perishable goods or limited edition products, as the authentication window itself has an expiration date.

The process of verification is a blend of classic microbiology and modern biotechnology. To authenticate a product, a sample is simply swabbed from its surface and placed in a portable growth medium. Within hours, the microbes multiply. The sample is then inserted into a handheld DNA sequencer, a device that is becoming increasingly affordable and field-deployable. The sequencer reads the genetic code of the microbes, and software compares it to a secure, encrypted database of legitimate sequences. A match confirms authenticity; a discrepancy or absence flags a potential counterfeit.

The advantages of this biological approach are profound. The level of security is exponentially higher than that of conventional methods. Copying a physical hologram is one thing; replicating a specific, living biological system with a precise genetic sequence requires a sophisticated biolab, deep expertise in synthetic biology, and knowledge of the exact microbial host and conditions—a barrier far too high for most counterfeiters. Furthermore, the tags are inherently sustainable. They are based on natural, biodegradable organisms, leaving no electronic waste or complex chemical residues behind, aligning with the growing demand for green technology solutions.

This technology also offers unparalleled traceability. In supply chains, especially for high-value goods like pharmaceuticals, luxury items, or aerospace components, a microbial tag applied at the source can provide an unbroken biological audit trail. Every handoff, from manufacturer to distributor to retailer, can be logged and verified, creating a "living ledger" that is incredibly difficult to falsify. This could revolutionize logistics, providing absolute certainty about a product's journey and handling.

However, the path to widespread adoption is not without its hurdles. Significant challenges remain in standardizing the microbial strains and genetic constructs to ensure they are stable, safe, and non-transferable to other environments. Public perception is another critical frontier; the idea of purposefully applying microbes to consumer goods, even benign ones, may require careful educational campaigns to overcome the "yuck factor" and assure consumers of absolute safety. Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA will also need to develop entirely new frameworks for approving these living tags, particularly for use on food, medical devices, and pharmaceuticals.

Despite these challenges, the momentum is building. Several biotechnology startups and university research consortia are already in advanced stages of developing pilot programs with partners in the pharmaceutical and luxury goods sectors. Early prototypes of field-deployment kits for law enforcement and customs agents are being tested, aiming to put the power of genetic verification in the palm of their hands. The convergence of cheaper DNA synthesis, faster sequencing, and advanced bioinformatics is creating a perfect storm for this technology to transition from the lab to the market.

Looking forward, the implications extend far beyond anti-counterfeiting. The same principles could be used to create biological watermarks for digital media, where a physical microbial tag is linked to a digital asset, or to develop smart materials that can self-report their origin or degradation. The merger of biology and cryptography is opening a new chapter in security, one where the very building blocks of life become guardians of authenticity in our manufactured world.

In conclusion, while the concept of smearing bacteria on a watch or a medicine bottle to prove it's real might seem like science fiction, it is rapidly approaching commercial reality. Microbial gene sequence anti-counterfeiting represents a paradigm shift, moving security from the realm of the physical and digital into the biological. It promises a future where the most sophisticated security system is not made of silicon or ink, but is quite literally, alive.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025