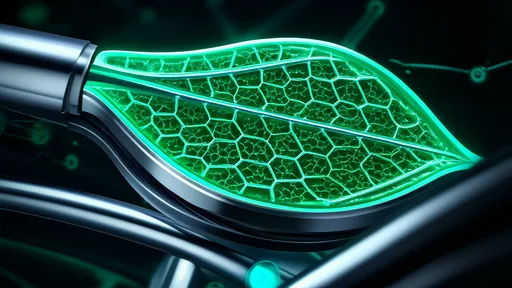

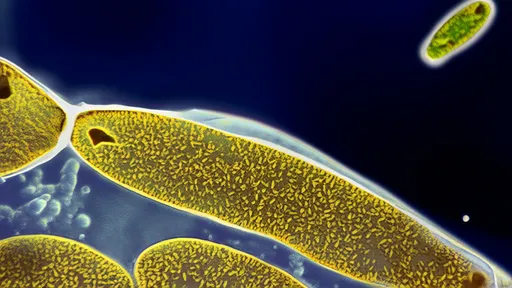

In the relentless pursuit of sustainable energy solutions, a groundbreaking frontier has emerged at the confluence of materials science and synthetic biology. Scientists are now looking beyond traditional silicon-based photovoltaics, turning their gaze towards the most proficient energy converter known to nature: the chloroplast. The intricate machinery within these biological powerhouses has inspired a revolutionary approach—designing artificial photosynthetic systems using Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) to mimic their elegant structure and function. This isn't merely an imitation of form; it's an ambitious endeavor to capture the essence of photosynthesis and repurpose it for human energy needs, offering a potential pathway to clean fuel production and carbon sequestration.

The core challenge in artificial photosynthesis has always been efficiency and stability. Natural photosynthesis is a staggeringly complex dance of photons, electrons, and molecules, orchestrated within the highly organized environment of the thylakoid membranes in chloroplasts. Early artificial systems, often based on homogenous solutions or simple semiconductor electrodes, struggled to replicate this spatial organization. They suffered from rapid charge recombination, where the energy from absorbed light is wasted as heat before it can be used for chemical reactions, and poor selectivity in producing the desired fuels, like hydrogen or hydrocarbons.

Enter Metal-Organic Frameworks. MOFs are crystalline porous materials composed of metal ions or clusters coordinated to organic linkers. Their defining characteristic is an extraordinary surface area and a degree of structural tunability that is virtually unmatched by other materials. By carefully selecting the metal nodes and organic ligands, chemists can precisely engineer the pore size, shape, and chemical environment within a MOF. This makes them an ideal candidate for constructing a synthetic analogue of the chloroplast. The MOF's porous structure can act as the scaffold, mimicking the confined and ordered space of the thylakoid lumen, where the light-dependent reactions occur.

The design philosophy is profoundly biomimetic. Researchers are not just putting photosynthetic components into a MOF; they are designing the MOF to be an integral part of the photosynthetic apparatus. One strategy involves incorporating light-harvesting complexes directly into the framework. This can be achieved by using photoactive organic ligands or by post-synthetically grafting molecular chromophores into the pores. The result is an antenna system that captures light energy with high efficiency and, crucially, funnels that energy through the framework via energy transfer mechanisms to designated catalytic sites, much like chlorophyll molecules transfer energy to a reaction center.

At these catalytic sites lies the heart of the process: water splitting and carbon dioxide reduction. The MOF's pores can be engineered to host molecular catalysts, such as cobalt or nickel complexes for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER), or platinum and cobalt oxides for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER). For CO₂ reduction, catalysts based on copper or rhenium can be embedded. The MOF's environment protects these often-sensitive catalysts from degradation, improves their solubility and dispersion, and can even enhance their activity by providing a preferential local chemical environment. Most importantly, the framework's structure ensures that the light-harvesting units and the catalytic centers are held in close, fixed proximity. This drastically reduces the distance an electron must travel, minimizing energy-wasting recombination and maximizing the quantum yield of the chemical reaction.

The parallels to the natural system are striking. In a chloroplast, the proteins Photosystem II and Photosystem I are perfectly positioned to hand off electrons in the Z-scheme of photosynthesis. In a MOF-based artificial leaf, the engineered pathway for electron flow from antenna to catalyst achieves a similar, streamlined efficiency. Furthermore, the porous nature of the MOF allows for the diffusion of reactants (water, CO₂) into the structure and the products (oxygen, hydrogen, formate, methanol) out, preventing product inhibition and allowing for continuous operation.

Recent breakthroughs have moved this technology from theoretical concept to laboratory reality. Teams around the world have demonstrated prototype MOF-based artificial photosynthetic systems. For instance, a UiO-type MOF incorporated with a ruthenium-based photosensitizer and a catalytic cobaloxime complex showed remarkable activity for hydrogen production from water under visible light illumination. Another system used a MIL-101 MOF to host both a light harvester and an enzyme for CO₂ reduction, creating a hybrid semi-biological system. These prototypes, while still operating on a small scale and often requiring sacrificial electron donors, provide crucial proof-of-concept. They validate the core idea that a well-designed MOF can provide the necessary organization to drive complex, multi-step photochemical reactions with an efficiency that begins to approach biological systems.

Despite the exciting progress, the path to commercialization is laden with challenges. The long-term stability of these materials under constant illumination in aqueous, sometimes corrosive, environments is a primary concern. The scalability of synthesizing these highly complex and precise crystalline materials cost-effectively is another significant hurdle. Furthermore, the overall solar-to-fuel efficiency of the best current systems still lags behind natural photosynthesis and is far from the benchmarks required for economic viability. Future research is intensely focused on developing more robust MOFs using cheaper, earth-abundant metals, creating more efficient and broader-spectrum light-harvesting systems, and engineering the internal pore environment with even greater precision to control reaction pathways and improve selectivity for specific valuable fuels.

The implications of successfully developing an efficient artificial photosynthetic system are monumental. It promises a truly renewable and carbon-neutral energy cycle. By using sunlight to split water, we can produce hydrogen, a clean fuel. By using it to reduce CO₂, we can not only produce hydrocarbon fuels but also actively remove a potent greenhouse gas from the atmosphere, effectively closing the carbon loop. This technology could lead to the development of "artificial leaves"—scalable panels that, when placed in sunlight and water, continuously produce fuel, day and night, without the intermittency issues of solar PV. It represents a paradigm shift from generating electricity to directly generating storable chemical energy from sunlight.

In conclusion, the emulation of chloroplasts using metal-organic frameworks stands as a testament to the power of biomimicry. It is a field where chemistry, materials science, and biology converge to address one of humanity's most pressing challenges. While significant obstacles remain, the foundational research has laid a robust and promising pathway forward. The creation of a synthetic leaf is no longer a fantastical dream but a tangible, albeit complex, engineering goal. As research continues to refine these bio-inspired architectures, the vision of harnessing the sun's power as effortlessly as a plant does moves steadily closer to reality, potentially heralding a new era of sustainable energy.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025