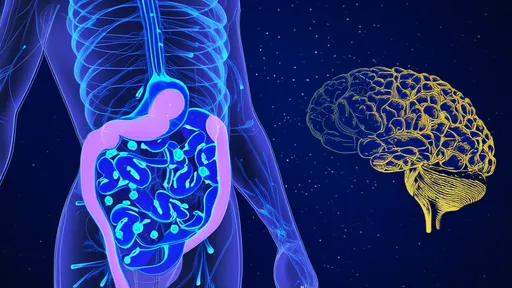

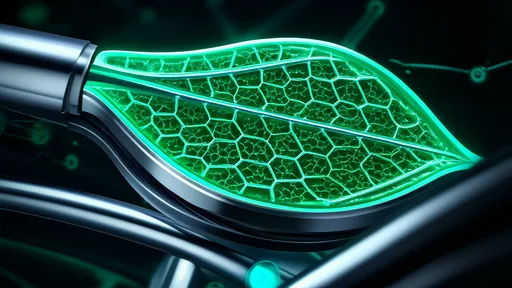

In the ongoing battle against climate change, scientists have turned their gaze toward the vast, untapped potential of the world's oceans. Among the most promising—and controversial—approaches is the concept of ocean iron fertilization, a geoengineering technique designed to enhance the ocean's natural carbon pump. The Southern Ocean, encircling Antarctica, has emerged as a primary focus for these efforts due to its unique biogeochemical properties and its critical role in global carbon cycling. This region, though rich in nutrients like nitrate and phosphate, is notably deficient in iron, a micronutrient essential for phytoplankton growth. By artificially adding iron to these iron-limited waters, researchers aim to stimulate massive phytoplankton blooms, which would absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. When these organisms die or are consumed, a portion of the carbon sinks to the deep ocean, effectively sequestering it away from the atmosphere for centuries. This process, known as the biological carbon pump, represents a potential lever to augment the ocean's capacity as a carbon sink.

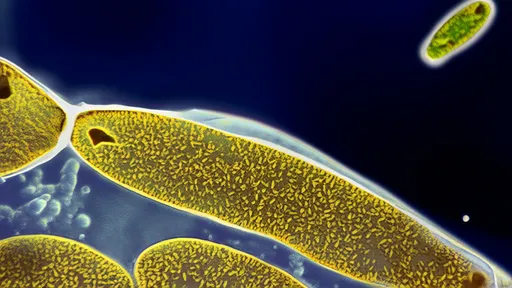

The theoretical foundation for iron fertilization rests on the landmark Iron Hypothesis, first proposed by oceanographer John Martin in the late 1980s. His famous quip, "Give me a half tanker of iron, and I will give you an ice age," vividly captured the profound climate impact this simple element could potentially wield. The hypothesis posits that during past ice ages, increased dust deposition delivered iron to the Southern Ocean, fueling phytoplankton growth that drew down CO₂ and contributed to global cooling. Modern experiments, beginning with IRONEX in 1993 and followed by a series of others like SOIREE and LOHAFEX, have consistently demonstrated that adding iron to these waters does indeed trigger blooms. Satellite imagery from these studies shows vast swathes of chlorophyll-rich green water appearing in the iron-fertilized patches, providing clear visual proof of concept. The blooms are not just superficial; they involve a complex shift in the ecosystem, often dominated by diatoms, which are silica-shelled phytoplankton particularly effective for carbon export due to their relatively heavy, fast-sinking cells.

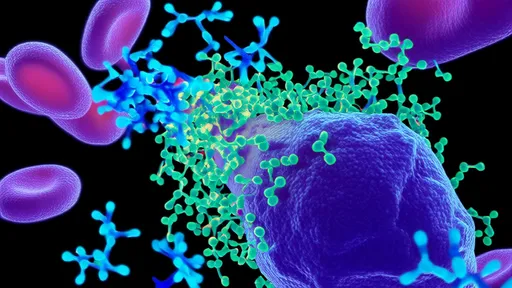

However, translating a successful small-scale experiment into a viable, large-scale carbon sequestration strategy is fraught with scientific and logistical challenges. A central issue is the efficiency of carbon export. While the surface bloom is undeniable, a significant portion of the fixed carbon is often recycled in the surface layer by bacteria and zooplankton, respired back into the atmosphere as CO₂, and never makes it to the deep ocean. The fraction that does sink, known as the export flux, is highly variable and depends on a multitude of factors. The composition of the phytoplankton community is paramount; diatom-dominated blooms generally export more carbon than those dominated by smaller, non-silicious species. The structure of the food web also plays a crucial role. The presence of certain types of zooplankton that produce fast-sinking fecal pellets can enhance export, while other grazers might simply respire the carbon. Furthermore, the physical oceanography of the Southern Ocean, with its powerful currents and deep mixing layers, can disperse the fertilized patch and its associated bloom, diluting the effect and potentially transporting nutrients away from the ideal sequestration zones.

Beyond the question of efficacy lies a formidable array of ecological risks and unintended consequences. Artificially manipulating a foundational aspect of the marine ecosystem is a monumental intervention. A primary concern is the potential for harmful algal blooms (HABs). Some phytoplankton species produce potent toxins that can accumulate in the food web, poisoning marine life and potentially impacting fisheries and even human health. Even non-toxic blooms can have detrimental effects. As the massive bloom of phytoplankton dies off and sinks, its decomposition by bacteria consumes dissolved oxygen, creating large, deep-water zones of hypoxia or even anoxia. Such oxygen minimum zones can devastate benthic (seafloor) ecosystems, killing organisms that cannot escape and altering the biodiversity of these fragile habitats. There is also the risk of altering nutrient cycles beyond the target area. A large-scale fertilization could draw down not just carbon but also essential nutrients like nitrogen, silicon, and phosphorus in the surface waters. As these nutrient-depleted waters are carried by currents to other ocean regions, such as the low-latitude tropics, they could actually inhibit primary productivity elsewhere, inadvertently reducing the natural carbon sink capacity of other parts of the global ocean.

The legal and governance landscape for ocean iron fertilization is as murky and turbulent as the Southern Ocean itself. There is no dedicated international legal framework that explicitly permits or prohibits large-scale commercial OIF. Instead, a patchwork of agreements comes into play. The London Convention and its London Protocol, which regulate ocean dumping, are the primary instruments. The LC/LP has issued non-binding resolutions stating that OIF activities, except for legitimate scientific research, should not be allowed. However, the definitions of "legitimate research" and "large-scale" are subjects of intense debate. The UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) has also adopted decisions calling for a precautionary approach, effectively recommending a moratorium on commercial geoengineering activities until a robust regulatory system is in place. This legal ambiguity creates a significant hurdle. Without clear, internationally agreed-upon rules governing permission, monitoring, verification, and liability, the door is open for rogue actors to proceed unilaterally, potentially causing transboundary environmental harm and sparking international disputes. The development of a transparent and scientifically rigorous regulatory regime is a prerequisite for even considering OIF as a serious climate tool.

Given the immense complexities and uncertainties, the future of iron fertilization in the Southern Ocean hinges on a rigorous and cautious path forward. The scientific community largely agrees that further targeted research is essential. Future experiments must be designed to answer the critical outstanding questions: What are the long-term fates of the sequestered carbon? How can we maximize export efficiency and minimize ecological side effects? How do we scale up from a 100-square-kilometer patch to a basin-wide application? This research must be coupled with the development of sophisticated monitoring and verification technologies. Remote sensing from satellites can track surface blooms, but assessing the carbon flux to the deep ocean requires autonomous underwater gliders, sediment traps, and biogeochemical Argo floats that can operate in the harsh Southern Ocean environment for extended periods. This data is crucial not only for science but for any future carbon accounting system. Ultimately, iron fertilization should not be viewed as a silver bullet but as one potential component in a broader portfolio of climate solutions, which must be dominated by aggressive greenhouse gas emissions reductions. The decision of whether to ever deploy it at scale will be as much a societal and ethical one as it is a scientific one, weighing a potential climate benefit against the profound responsibility of deliberately engineering our planet's largest ecosystem.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025