In the shadow of restless volcanoes, where the very air shimmers with heat and the ground trembles with pent-up fury, a quiet technological revolution is unfolding. For decades, monitoring these extreme environments meant relying on instruments with severe limitations—ones that would falter, melt, or fail just as the volcanic activity reached its most critical phase. The need for robust, reliable sensing technology in such infernal conditions has long been a paramount challenge for volcanologists and engineers alike. Today, that challenge is being met not by incremental improvements, but by a fundamental shift in material science, centered on a remarkable substance: silicon carbide.

The core of the problem has always been the environment itself. Volcanoes present a combination of factors that are uniquely hostile to conventional electronics. Temperatures near lava flows or within fumaroles can easily exceed 600 degrees Celsius, a point at which silicon, the foundation of most modern semiconductors, begins to behave unpredictably and ultimately fails. Furthermore, the highly corrosive gases—such as sulfur dioxide, hydrogen chloride, and hydrogen fluoride—quickly degrade metal contacts, protective casings, and sensor membranes. Add to this the abrasive ash, intense radiation, and immense physical pressure, and it becomes clear why gathering continuous, high-fidelity data from the very heart of volcanic activity has been nearly impossible. The loss of these sensors doesn't just represent a financial cost; it means losing invaluable data right when it is most needed to predict eruptions and save lives.

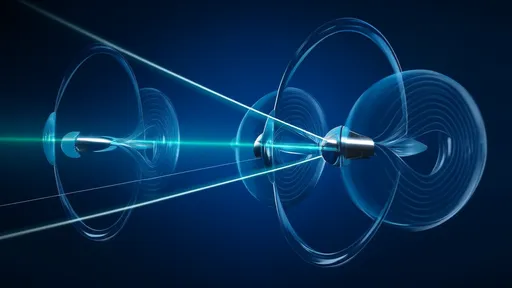

This is where silicon carbide (SiC) enters the story. Unlike its silicon-based counterparts, SiC is a wide-bandgap semiconductor. This fundamental property makes it exceptionally resistant to heat. Where a silicon chip would succumb, a SiC chip can continue to operate reliably at temperatures well above 600°C, with some designs pushing the boundaries even further. But its resilience doesn't stop at thermal tolerance. Silicon carbide possesses a remarkable chemical inertness. It is highly resistant to corrosion from the very acids and compounds that rapidly destroy other materials, making it ideally suited to withstand the toxic atmospheric soup surrounding volcanic vents. Its inherent mechanical strength and resistance to radiation complete the profile of a material seemingly engineered for extreme earth science.

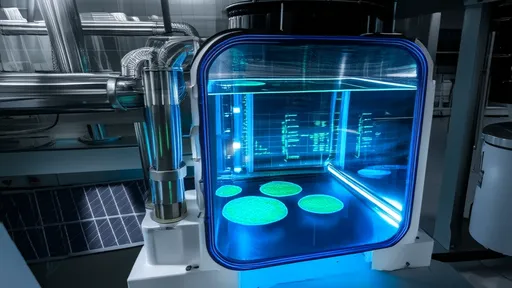

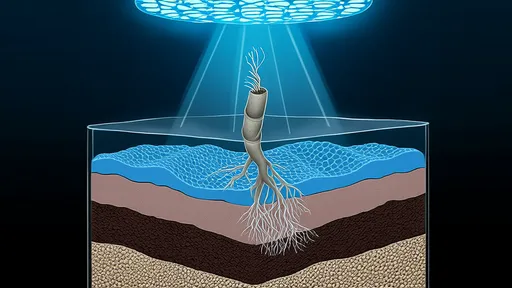

The application of this technology is most evident in the development of a new generation of in-situ sensors. These aren't instruments placed at a safe distance; they are designed to be deployed directly onto lava domes, near active vents, or even within gas plumes. At their heart are SiC-based chips that act as the core processing units. These chips can manage a suite of miniature sensors designed to measure a multitude of parameters simultaneously. They are built to measure the intense heat radiating from freshly extruded lava, analyze the precise composition of escaping gases in real-time, detect subtle changes in ground deformation through integrated micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS), and monitor for the tell-tale seismic tremors that often precede a major eruptive event.

The data these hardy little sentinels collect is nothing short of transformative. Volcanology has historically relied on extrapolation and models built from distant, and often sporadic, measurements. With SiC sensors providing a continuous, real-time stream of data from inside the danger zone, scientists can now observe the intricate processes of a volcano's unrest as they happen. They can track the rise of magma by noting minute changes in gas chemistry and temperature. They can witness the building of pressure by monitoring micro-seismic activity and ground tilt with unprecedented clarity. This is no longer just forecasting; it is direct observation of a volcano's vital signs, leading to predictive models of vastly improved accuracy and reliability.

Perhaps the most profound impact of this technology is on early warning systems and risk mitigation. The ability to have always-on, unfailing monitors in the most hazardous areas provides communities living in the shadow of volcanoes with something invaluable: time. More accurate and earlier predictions of eruptions allow for timely evacuations, potentially saving thousands of lives. Furthermore, the durability of SiC sensors means a single deployment can provide data over extended periods, even years, building long-term baselines of activity that are crucial for understanding a volcano's unique personality and behavior patterns. This moves disaster response from a reactive to a proactive stance.

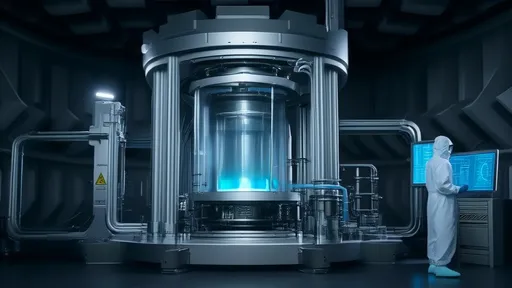

Of course, the path from laboratory breakthrough to volcanic deployment is not without its hurdles. The design and packaging of these sensors present immense engineering challenges. Creating connections and enclosures that can match the resilience of the SiC chip itself is a complex task. Powering these remote systems for long durations in environments where maintenance is impossible requires innovative solutions, likely involving energy harvesting from thermal gradients or advanced long-life batteries. Finally, the cost of developing and manufacturing these highly specialized systems remains significant, though it is expected to decrease as the technology matures and finds wider adoption.

Looking beyond the smoldering craters of Earth's volcanoes, the potential applications for silicon carbide electronics are stellar. The same properties that make SiC perfect for hellish volcanic environments also make it a prime candidate for the harsh conditions of space exploration, the intense heat within jet engines, and the demanding requirements of next-generation nuclear reactors. The work being done today to listen to the heartbeat of volcanoes is, in essence, pioneering a new class of electronics that will allow us to explore, monitor, and operate in the most extreme frontiers imaginable.

In conclusion, the integration of silicon carbide chip technology into volcanic monitoring represents a paradigm shift in our relationship with one of nature's most powerful forces. It replaces fear and uncertainty with data and understanding. These robust sensors are more than just pieces of technology; they are our avatars, standing where we cannot, enduring what we cannot, and sending back the secrets they learn from the edge of the inferno. This is not merely an advancement in geoscience; it is a testament to human ingenuity's ability to extend its reach into the most hostile corners of our planet, making us all safer in the process.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025