Deep beneath the Antarctic ice sheet, where darkness and extreme cold have persisted for millions of years, scientists have uncovered a hidden world that challenges our understanding of life’s resilience. In one of the most ambitious and technologically demanding research endeavors of the decade, an international team has successfully sequenced genetic material from microorganisms isolated in a subglacial lake for an estimated five million years. This extraordinary discovery not only sheds light on the adaptability of life in one of Earth’s most hostile environments but also carries profound implications for the search for extraterrestrial life on icy moons like Europa and Enceladus.

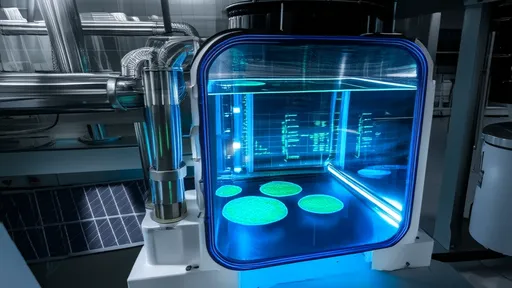

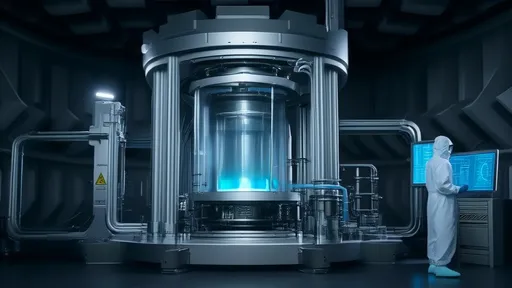

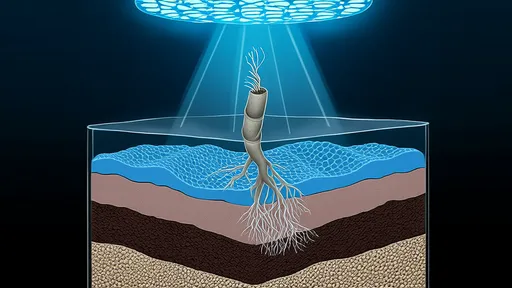

The project, part of a broader effort to explore Antarctica’s subglacial hydrological network, targeted a lake buried under nearly four kilometers of ice. Accessing such an environment required meticulous planning and innovative engineering to prevent contamination of the pristine ecosystem. Using a hot-water drill specially designed to minimize microbial intrusion, researchers carefully penetrated the ice sheet to retrieve water and sediment samples from the lake’s ancient depths. The samples were then analyzed using advanced metagenomic sequencing techniques, allowing scientists to reconstruct the genetic blueprints of organisms that have evolved in complete isolation for millennia.

The findings reveal a microbial community that has thrived in total darkness, at freezing temperatures, and under high pressure, with no energy input from the sun. Instead of photosynthesis, these organisms utilize chemosynthesis, deriving energy from inorganic compounds such as methane and sulfur. The genetic data indicate a highly specialized and slow-evolving ecosystem, with microbes possessing unique adaptations for nutrient recycling and energy conservation. Some of the genes identified are involved in repairing DNA damage caused by the extreme conditions, while others code for enzymes that break down minerals in the bedrock—a process that may serve as the foundation of the food web in this lightless world.

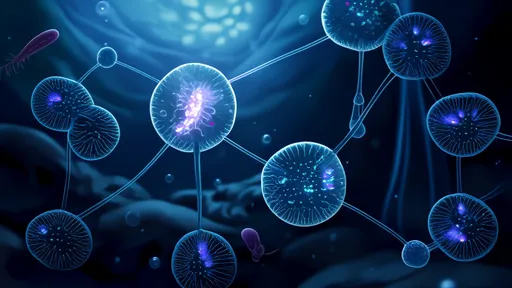

What makes this discovery particularly remarkable is the timescale of isolation. Five million years of separation from the rest of the biosphere have allowed these microorganisms to evolve along a distinct trajectory, unaffected by external evolutionary pressures. The genetic sequences show little homology with known species, suggesting that many of these microbes represent entirely new branches on the tree of life. This has excited evolutionary biologists, who see the lake as a natural laboratory for studying long-term microbial evolution and adaptation.

Beyond its biological significance, the study offers a glimpse into how life might persist in similar environments elsewhere in the solar system. Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus, for instance, are believed to harbor vast liquid water oceans beneath their icy shells. The conditions in Antarctica’s subglacial lakes are among the closest analogues on Earth to these extraterrestrial settings. The ability of life to survive and diversify in such isolation strengthens the case for the potential habitability of icy moons. If microorganisms can endure millions of years cut off from the surface, using only geochemical energy sources, then similar ecosystems might exist beyond Earth.

However, the research also raises ethical questions about the exploration of these fragile environments. The very act of drilling into subglacial lakes carries a risk of contamination, both from introducing surface microbes into the lake and from bringing up previously unknown organisms that could have unintended effects if released. The team adhered to strict sterility protocols, but as interest in these ecosystems grows, so does the need for robust planetary protection guidelines—lessons that will be critical for future missions to other worlds.

Looking ahead, scientists are eager to expand this research to other subglacial lakes across Antarctica, each of which may host unique ecosystems shaped by different geological and chemical conditions. Some lakes are thought to be even older, possibly harboring life forms that have been isolated for tens of millions of years. Comparative studies could reveal how varying degrees of isolation influence evolutionary outcomes and whether there are common strategies that life employs to survive in extreme cold and darkness.

This groundbreaking genetic sequencing effort marks a new chapter in both polar biology and astrobiology. It demonstrates that life, in its simplest forms, can persist under conditions once thought insurmountable, expanding the boundaries of where we might expect to find it. As technology advances, allowing for more detailed genomic and metabolic analyses, we may soon uncover even deeper secrets hidden beneath the ice—secrets that could redefine our place in the universe.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025