In the rarefied air of the stratosphere, twenty kilometers above Earth's surface, a quiet revolution in microbiology is unfolding. For decades, scientists considered this atmospheric layer a near-sterile boundary, a buffer zone between the tropospheric weather systems below and the cosmos beyond. Recent advances in high-altitude sampling technology, however, have shattered this assumption, revealing a surprising diversity of microbial life drifting on global air currents. The discovery of these resilient communities has ignited a fascinating new field of study: stratospheric microbial gene flow, a process that may fundamentally alter our understanding of global genetic exchange, ecological resilience, and even the origins of life itself.

The technical feat of capturing these microscopic stratospheric travelers cannot be overstated. Research teams employ specially designed balloons and high-altitude aircraft equipped with sophisticated, sterile sampling apparatus. These devices must function in extreme cold, under intense ultraviolet radiation, and at pressures barely one-tenth of those at sea level. The goal is to collect particulate matter without contamination from the craft itself or from lower atmospheric layers during ascent. Each successful mission retrieves a precious cargo of dust, ice crystals, and other aerosols, which are then subjected to rigorous genetic analysis in laboratories on the ground.

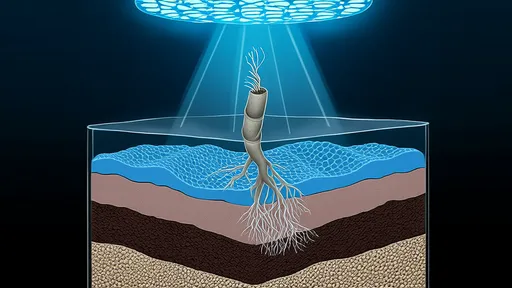

Initial genetic sequencing of these samples has yielded a trove of unexpected data. The stratosphere is not a barren wasteland but a dynamic reservoir of microbial diversity. Researchers have identified genetic signatures from a wide array of bacteria and fungi, including species commonly found in soil and ocean surfaces. The pivotal question is how these organisms arrive at such incredible altitudes. The prevailing theory points to powerful vertical transport mechanisms, such as volcanic eruptions, massive dust storms, and even severe thunderstorms with strong updrafts that can inject vast quantities of particulate matter from the Earth's surface into the upper atmosphere. These events essentially create a planetary-scale elevator, lifting microbes on a one-way trip into the sky.

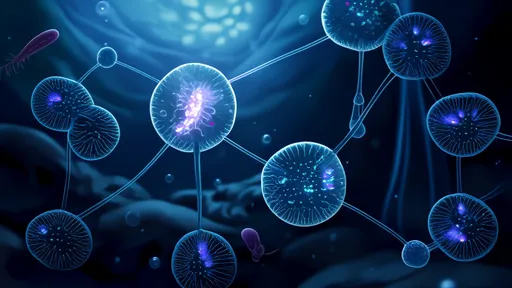

Survival in this harsh environment is a testament to extraordinary biological adaptation. The stratosphere subjects its inhabitants to a brutal combination of factors: desiccating conditions, temperatures far below freezing, and unfiltered solar and cosmic radiation that shatters DNA. Yet, the genetic evidence shows that many of these microbes are not only present but often metabolically active, existing in a dormant state or potentially even repairing damage. Many possess unique genetic adaptations, such as enhanced DNA repair mechanisms, robust protective endospores, or pigments that act as biological sunscreens. They are the ultimate extremophiles, thriving where few other life forms could persist for more than a moment.

This discovery forces a radical rethinking of the biosphere's boundaries. We can no longer view ecosystems as confined to the land, sea, and lower air. The stratosphere must now be considered a legitimate, global-scale biome—the "aerobiome." This high-altitude ecosystem functions as a continuous, planet-wide conveyor belt for microbial genetic material. A microbe lifted by a dust storm in the Sahara could potentially drift for weeks before descending in a rainfall event over the Amazon rainforest, thousands of kilometers away. This process, termed intercontinental genetic drift, suggests a level of global connectivity between terrestrial and marine ecosystems that was previously unimaginable.

The implications for gene flow are profound. The stratosphere acts as a massive, slow-motion mixing chamber for the planet's genetic library. Genes that confer advantages—such as antibiotic resistance, novel metabolic pathways for breaking down pollutants, or traits for surviving extreme environments—can be dispersed globally through this high-altitude pathway. A beneficial mutation arising in a remote region could, in theory, be shared across continents via this atmospheric route, bypassing traditional geographic barriers like oceans and mountain ranges. This challenges classical models of evolution and biogeography, which are largely based on geographically isolated populations.

Beyond Earthly concerns, this research profoundly impacts the field of astrobiology. The conditions in the Earth's stratosphere are the closest analog we have to the surface of Mars or the high atmosphere of Venus. Understanding how life persists and its genetic material disperses in our own upper atmosphere provides a critical framework for predicting where and how we might find life on other planets. Furthermore, it fuels the theory of panspermia—the idea that life could be distributed throughout the universe by hitchhiking on asteroids, comets, or dust particles. If microbes can journey between continents in our sky, perhaps they can also journey between planets.

Looking ahead, the future of stratospheric biological sampling is incredibly promising. Next-generation projects aim to conduct in situ genetic sequencing on sampling platforms themselves, eliminating the risk of contamination during descent and providing real-time data. International collaborations are forming to create a global network of monitoring stations to track the flow of biological material through the atmosphere over time. This data will be invaluable for modeling the spread of pathogens, understanding the ecological impact of climate change on global dispersal patterns, and perhaps even providing early warning systems for disease outbreaks or invasive species.

The discovery of a vibrant microbial ecosystem in the stratosphere and the subsequent study of its gene flow is a humbling reminder of life's tenacity and interconnectedness. It reveals that the air above us is not empty space but a living, breathing highway for genetic exchange that encircles the globe. This research dissolves the artificial boundaries we have drawn around ecosystems and forces us to adopt a more holistic, planetary perspective on biology, evolution, and the very distribution of life itself.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025