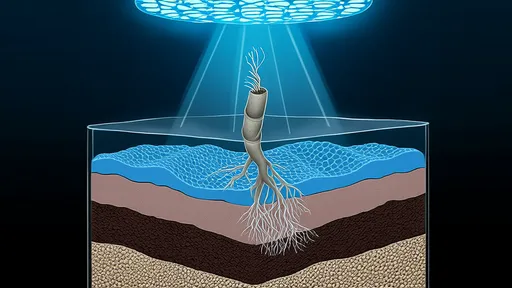

In the evolving landscape of agricultural and environmental sciences, the ability to visualize and analyze soil structure without causing disruption has long been a sought-after capability. Traditional methods of soil analysis, while informative, often involve extraction and laboratory processing that alter the very fabric of the sample, potentially skewing results and limiting understanding. A transformative approach is now gaining traction, offering a window into the hidden world beneath our feet: non-invasive 3D imaging of soil architecture through root system laser scanning.

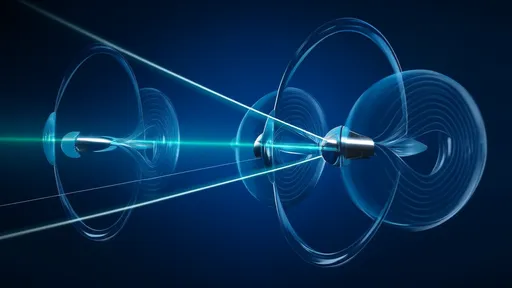

This technology, a sophisticated fusion of optics, robotics, and computational analysis, operates on the principle of laser triangulation or structured light scanning. A specialized apparatus, often mounted on a robotic arm or a gantry system, is maneuvered around an exposed soil profile or a prepared monolith. It projects a precise grid or pattern of laser light onto the surface. High-resolution cameras, positioned at known angles, capture the minute distortions of this pattern as it conforms to the complex topography of roots, pores, and aggregates. This captured data is not merely a surface image; it is a dense cloud of millions of individual points, each with a precise X, Y, and Z coordinate in space.

The raw point cloud is the digital clay from which the final model is sculpted. Powerful algorithms process this massive dataset, filtering out noise, aligning scans from different angles, and stitching them together into a seamless whole. The result is a highly detailed, three-dimensional digital replica of the soil structure. This model can be rotated, zoomed, and virtually dissected on a computer screen, allowing researchers to explore features like macroporosity, root architecture, and the spatial arrangement of soil particles in ways previously confined to the imagination. The resolution is astounding, capable of distinguishing features down to a fraction of a millimeter, revealing a labyrinthine world of incredible complexity.

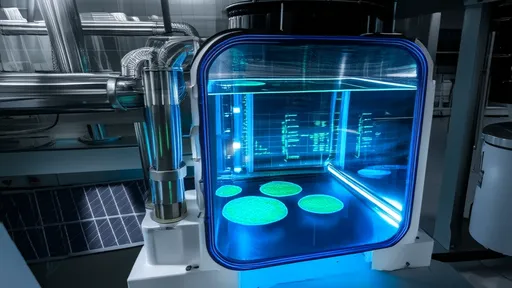

The implications of this non-destructive peek into the soil are profound and far-reaching. For agronomists, it provides an unprecedented tool to study root-soil interactions. They can now observe how a root system actually develops in its natural environment, how it navigates pores, seeks nutrients, and alters its surroundings without ever digging it up. This can lead to the development of more resilient crop varieties with root architectures optimized for specific soil conditions, water availability, or nutrient uptake. The technology allows for temporal studies as well; the same sample can be scanned repeatedly over time to monitor root growth dynamics, organic matter decomposition, and structural changes in response to management practices like tillage or cover cropping.

Beyond the farm, environmental scientists are employing this technology to tackle pressing challenges. In the realm of carbon sequestration, understanding the physical mechanisms that protect organic carbon within soil aggregates is crucial. Laser scanning can visualize these micro-environments, helping researchers predict how carbon storage might respond to climate change or different land-use strategies. In hydrology, the technology is used to model water infiltration and movement through soil pores, improving predictions of runoff, erosion, and groundwater recharge. It even finds application in remediation studies, where scientists can visualize the spread of contaminants or the growth of pollutant-degrading microbes in three dimensions.

Despite its powerful capabilities, the technique is not without its challenges and limitations. The process can be computationally intensive, requiring significant hardware power to process the vast datasets into usable models. The initial cost of the scanning equipment and the software platforms for analysis can be a barrier for some research institutions. Furthermore, while the method is non-invasive to the sample itself, it typically requires some level of preparation, such as carefully exposing a soil face or extracting an intact core, which, while minimally destructive, is not a purely in-situ field technique. Current research is focused on overcoming these hurdles, developing more portable and affordable systems, and refining algorithms to accelerate processing times and enhance automatic feature recognition, such as distinguishing live roots from dead organic matter or mineral particles.

As the technology continues to mature and become more accessible, its potential to revolutionize our comprehension of the critical zone—the vibrant skin of the Earth where rock, soil, water, air, and living organisms interact—is immense. It moves soil science from a discipline reliant on destructive sampling and two-dimensional sections to one that can preserve, analyze, and share intricate three-dimensional structures. This shift is not merely incremental; it is foundational, fostering a deeper, more holistic appreciation for the complex architecture that supports all terrestrial life. The view through the laser scanner is more than a high-tech image; it is a new lens for understanding the ground upon which we stand and grow.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025