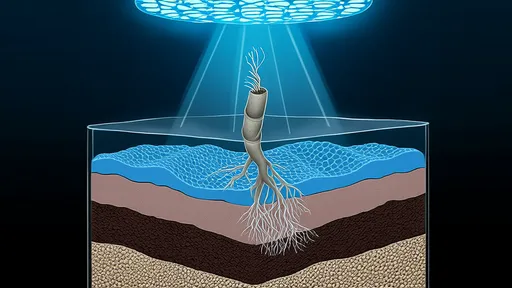

In the perpetual darkness of the deep ocean, where pressures crush and temperatures swing from near-freezing to scalding extremes, life not only persists but thrives in one of Earth’s most enigmatic ecosystems: hydrothermal vents. Here, in the absence of sunlight, a complex web of energy exchange unfolds, driven by chemosynthetic microorganisms. These remarkable life forms have mastered the art of harvesting energy from inorganic chemicals, forming the foundational layer of a food web that supports diverse and unique organisms. Central to their survival and function is a process known as extracellular electron transfer, a sophisticated mechanism that allows microbes to interact with their mineral-rich environment, exchanging electrons to power their metabolism.

The discovery of hydrothermal vents in the late 1970s revolutionized our understanding of life’s possibilities. Unlike photosynthetic ecosystems that rely on the sun’s energy, vent communities are powered by chemosynthesis, where microbes convert dissolved minerals and gases into organic matter. The key players in this process are chemosynthetic bacteria and archaea, which utilize chemicals such as hydrogen sulfide, methane, and hydrogen released from the Earth’s crust through vent fluids. These microorganisms serve as primary producers, analogous to plants in sunlit environments, and form symbiotic relationships with larger organisms like tube worms, clams, and shrimp, providing them with essential nutrients.

At the heart of chemosynthesis lies electron transfer, a fundamental biochemical process where electrons are moved between molecules, generating energy. In the context of deep-sea vents, this often involves extracellular electron transfer (EET), where microbes exchange electrons with solid substrates, such as minerals or other cells, outside their own membranes. This ability allows them to tap into a vast reservoir of chemical energy available in the vent environment. For instance, some microbes can oxidize iron or sulfur compounds, transferring electrons to external acceptors like iron oxides or even directly to other microbial species, creating an intricate energy network that sustains the entire ecosystem.

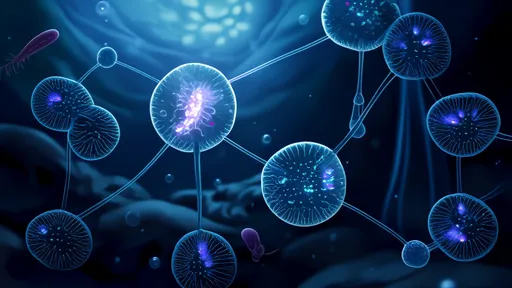

The mechanisms behind extracellular electron transfer are diverse and sophisticated. Some microorganisms employ direct contact, using specialized proteins on their cell surfaces to facilitate electron exchange with minerals or other cells. Others produce conductive nanowires, hair-like extensions that act as biological wires, enabling them to transfer electrons over micrometer-scale distances. Additionally, soluble electron shuttles, such as flavins or quinones, can be secreted by microbes to ferry electrons between cells and substrates, effectively extending their reach and influence within the environment. These strategies highlight the adaptability and innovation of deep-sea microbes in harnessing energy under extreme conditions.

Recent research has unveiled the surprising extent and complexity of these microbial energy networks. Studies using advanced genomic and electrochemical tools have identified numerous novel microbes capable of EET, many of which belong to previously unknown lineages. For example, certain archaea found in hydrothermal vents have been shown to engage in direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET), where electrons are passed between different species without the need for intermediate shuttles. This process enables syntrophic relationships, where one microbe consumes the waste products of another, optimizing energy efficiency and promoting community stability in the nutrient-limited deep sea.

The implications of these discoveries extend beyond deep-sea ecology. Understanding how microbes exchange electrons in extreme environments has potential applications in biotechnology, such as the development of microbial fuel cells, which generate electricity from organic waste. Moreover, studying these systems provides insights into the origins of life on Earth and the possibility of life on other planets, where similar chemosynthetic processes might occur in subsurface oceans or hydrothermal systems. The resilience and ingenuity of vent microbes challenge our definitions of life and highlight the untapped potential of Earth’s most remote habitats.

Despite significant advances, many questions remain unanswered. How do microbes coordinate electron transfer in complex, mixed-species communities? What role do viruses play in shaping these networks? How might climate change and human activities, such as deep-sea mining, impact these fragile ecosystems? Ongoing expeditions and interdisciplinary collaborations are essential to unraveling these mysteries. As technology improves, allowing for more detailed in situ measurements and experiments, we can expect to deepen our understanding of these microbial power grids and their global significance.

In the grand tapestry of life, deep-sea hydrothermal vents stand as a testament to nature’s creativity and resilience. The electron transfer networks forged by chemosynthetic microbes not only sustain vibrant ecosystems in the abyss but also offer a window into the fundamental processes that drive life on Earth and beyond. As we continue to explore these hidden worlds, we are reminded of the interconnectedness of all life and the endless possibilities that lie beneath the waves.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025